We live in an exciting age for videogames. There are games for all kinds of people, and with all kinds of associated messages, feelings and perspectives. Quite simply, they have become an art form.

Narratively, games have become the canvas for an exciting new breed of interactive storytelling – one that frequently involves a push and pull between the author and the audience, whether that’s an individual player or a community of players engaging with a broader mission that spans a long life multiplayer game.

The tools for writing games have also become more advanced, allowing budding writers to put digital pen to digital paper in easier ways than ever before. There has never been a better time to get into writing for games. With that in mind, we decided to put together some insight into how to get started.

Themes and tones

One of the most critical components of a successful videogame story is to be zeroed in on your themes and the tone you wish to convey. Tone is the easier of the two to figure out, as there are many recognisable tones we know and love in all forms of media: Scary, funny, epic, nostalgic, romantic, exciting, and many more. All of these tones have found their way into videogames in one form or another, and some are more common than others. Finding a unique combination can be one way to make your story more compelling and interesting.

Themes are a little harder to nail down, and that’s because they could be pretty much anything. But, your tone might help you figure it out. For example, a romantic tone probably means you’ll be dealing with the theme of love. And from love, maybe that means you’re dealing with themes of companionship, choice, loss, self-improvement, or strife. If you want your story to be epic in tone, then your themes must be huge as a reflection of that: Perhaps war, morality, sacrifice, power, or leadership. Most writers like to think about themes in terms of aspects of the human condition. By finding a link to universal human experiences, you make your story more relatable to the audience and give them things they can latch onto.

Keystone Events

There are lots of ways to write stories. But one way that follows on nicely from considering your themes is to come up with some critical events that form the essential milestones of your story. You’ll probably have at least 3, and a couple of them will probably be the beginning and end of your story, which we’ll discuss later in the article.

For now, think about how these events convey your themes and tone. You may have some events which are just cool things you would like to see happen in a game, and that’s okay too.

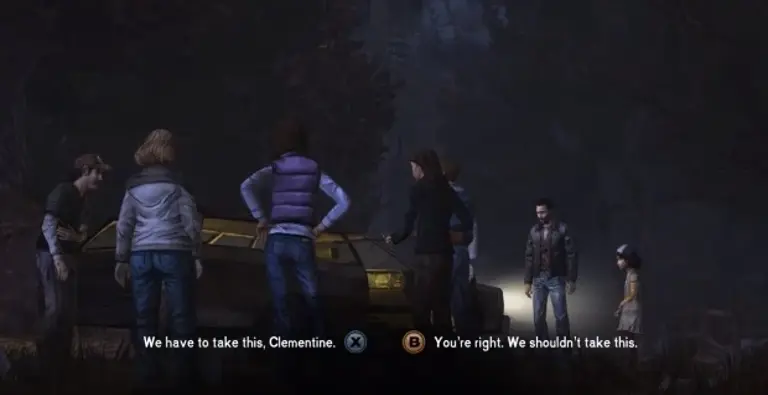

Maybe your theme is power, and one of your keystone events is a moment when that power is seized, unleashed, or lost. Maybe one of your themes is choice, and one such event could be a particularly dramatic moral dilemma you can present to a player as a choice they can actually make.

Settings

Once you’ve come up with some events, you’ve probably, without realising it, started to set up your setting and some of your characters. Let’s start with setting.

Some game stories trade very heavily on setting, intertwining the themes with the space that the story takes place in. A story about hubris might take place in a palace, a scary story about mortality might take place in an abandoned town, a swashbuckling story of adventure might take place in a jungle filled with hidden riches, raging rivers and deadly wildlife.

When considering setting, what you’re really doing is an act of worldbuilding – and the setting for your story is then typically a small slice of that overall world, which ideally you want players to want to explore. One world your story could take place in is the real one, our current reality – subject to all the laws of physics, power structures, urban planning and social conventions we have now. But, you are not bound to this.

If you’re creating a new world, your aim is to fill in the blanks:

- What does this world look like? The environment, the weather, the resources?

- What is this world actually like, under the surface? What would it feel like to live there, and what is the culture like? How do they communicate? Do they have religion? Nuclear families? Are they happy?

- Who rules, and how? What hierarchy is there for citizens of this universe? What gives people power over others in this place?

Creating a setting helps define how your characters might be, because they will presumably have grown up in the world you have created. It will have changed them. For the audience, the setting is a chance to show them something they haven’t seen before, and experience things they haven’t experienced before. Whether it takes place in our world, a similar world, or an entirely made up one, a game is a chance for people to explore a perspective that is not their own.

By now, you might’ve encountered one of the trickiest aspect of creativity: Naming things. The way in which humans name places and people is something you could study for a lifetime, and tapping into that to create memorable and effective names for characters, towns, cities and countries can be incredibly difficult. How do you ensure you pick a name like “Gordon Freeman”, and not something that sounds weird, like “Jim Man”? How do you name a town like “Whiterun” instead of “Purpleplace”?

One resource which might help is Gary Gygax's Extraordinary Book of Names. Gygax invented Dungeons & Dragons, which as you probably know, has a lot of named places and people. It’s primarily written with fantasy worlds in mind, but it’s incredibly useful for using what you now know about your setting to help define what likely names would be - based on the way your fictional society operates, and it’s underpinned by a strong understanding of language.

“Life goes on...”

One last note about settings: An important principle for most stories is the idea that life goes on within it. That is, typically, when your characters look away or leave an area, life as you’ve defined it continues to exist in that space. A story doesn’t feel real if all the secondary characters are just standing there waiting for the main character to act. They should have lives, routines, hobbies, jobs, families, and their own goals and dreams.

Character

At this point you’ve hopefully started to formulate some idea of what some of your characters will be. You’ve thought about the context they live in and how that might shape them. You’ve thought about some of the events that will help define them, and possibly how they’ll react. You may have even given them names. That’s getting pretty close to a fleshed out character!

Before we move on though, make sure you consider their traits. Specifically, you want every main character (and most of your side characters) to have identifiable and distinct traits from each other. It doesn’t work to just have four characters and all you can say about them is “they’re the good guys, doing the right thing”. This becomes especially important in the context of long life multiplayer games, which increasingly have a focus on characters. Yes, these differing heroes have unique abilities, but they should also have unique personalities.

You may already have some traits in mind, defined by those keystone events and how you want the characters to react to them, but take some time to map out the traits. One good exercise is to see whether you think someone could describe the character to you without saying their name or actions that they do specifically. If someone would be able to say “Oh, them? They act cunning, calculating and ruthless at first glance. But they secretly have feelings and eventually do what’s right.” – what you’ve just described is probably a Han Solo cliché but it’s a lot better than someone you cannot describe at all.

Your cast has room for all sorts: From stoic to the overly emotional, intelligent to stupid, good to evil, chaotic to lawful, wounded to prideful, levels of social awkwardness, and everything in between. For player characters, bear in mind that the game mechanics might afford them choices, which means they might not be played exactly how you, the author, would have played them. Sometimes games opt for quiet, almost generic protagonists that allow the player to imagine themselves as the avatar presented.

Next, some of your characters need arcs. You may have already defined most of an arc when considering your keystone events, but a full arc is an understanding of the journey that specific character is going on in terms of their outlook and who they are. Events are part of it, as the events that happen to us influence who we become, but an arc is more than that. Arcs involve something fundamental about the character being altered. Common arcs include redemption, revenge, acceptance, and taking on responsibility. They also often involve the character learning moral lessons from their experiences, pushing them further towards goodness or towards villainy. Think also about the feelings this might elicit from someone playing as that character, if they’re the one people might play as.

“Representation matters.”

Before we move on to how these arcs help form the basis of narrative, one last note about characters. We’ve talked a little about diversity of traits when putting together a cast of characters, but it’s also important to consider actual diversity: Diversity of gender, heritage, sexual orientation, ability, and ethnic background. Players (and all who consume stories) yearn to relate to characters, to imagine what it would be like to be them. If your story only caters for one type of person, then you are failing as a game writer.

Representation matters, regardless of how big you may think the demographics are. Character creators that some games offer may give some agency to players to define how their avatar looks, but there remains a responsibility on you to ensure that at every opportunity in the dialogue, in the supporting cast, in the depictions of culture – that you are being fair. Your characters can be offensive. But you, the author, should not be.

Narrative structure

It’s all coming together. We have a setting, and we have characters – we even know what’s going to happen to some of them, which is the basis for narrative.

There are a number of ways to think about narrative. One classic that’s still regularly referenced is Propp’s theory, which is based on analysis of Russian folktales and has defined a common structure by which stories are often told. These building blocks and character tropes can be useful for fleshing out a narrative.

In the world of film, we’re accustomed to the concept of a three act structure (sometimes split over three films, as a trilogy): Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution. That might work for you. But games are typically longer than films, often even longer than trilogies of them. As a result, some have looked to television for inspiration on structure, and long lasting games have taken to the concept of “seasons”, treating each season as a mini-narrative unto itself with a beginning, middle and end.

One thing to consider is that you don't necessarily need to be limited by the screen. These days, the most successful videogames are multimedia franchises in their own right, extended experiences which incorporate websites, books, comics, podcasts, and more. Be mindful that while you do have to present something cohesive for people who only play the game, your overall remit could be broader.

Whatever mechanism you use for structure, there are some tenets you can use to guide you as you progress from point A to point B. First is the idea of irreversible change. In games, this can be a powerful motivator for forward momentum and future progress, and narratively it pushes your characters into new and unfamiliar spaces. Irreversible changes can include death, true love, the loss or destruction of an item, or physical changes to the landscape. It could even be uncovered knowledge, paired with what you know about your characters. Would your characters say “We can’t go back because of X. We have to go forward.”?

Irreversible change often leads to escalation, which is good because videogames also tend to favour escalation in terms of their approach to challenge, and it fits together nicely to escalate in your narrative too. As your story escalates, more irreversible changes occur, and more is put at stake. One good way to reflect escalation in your setting is to tie it to geographical scope. Consider an RPG which has you start in a small village. The story could take you to a town, then a city, until perhaps you end up conquering the entire country. By tying escalation to the physical space you make it easy for players to retrospectively look back and think “Wow, look how far I’ve come!”, which is a rewarding feeling.

“Twists are narrative dynamite, by two definitions: They can make an exceptionally interesting story and encourage replayability, but they can also blow up in your face.”

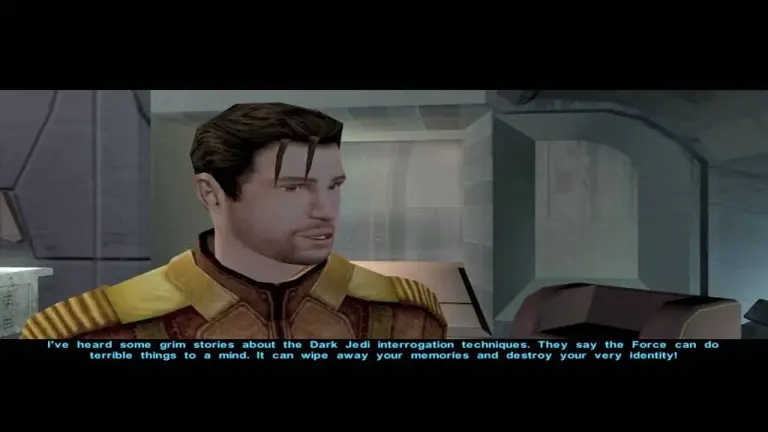

One form of narrative change is a twist. Twists are narrative dynamite, by two definitions: They can make an exceptionally interesting story and encourage replayability, but they can also blow up in your face. A good twist re-contextualises everything the player has seen up until this point. A bad one leaves them confused and angry.

The trick to successful twisting is to make the twist feel earned, by hinting at it long before it’s revealed, but that is where it becomes challenging: If you overplay your hand and players see it coming, it’s ruined. You must also consider the potential twists have for causing plot holes, because if a rug is pulled from under you, you always want to feel like you standing on the rug in the first place was a logically consistent starting point, and that the rug being moved now makes sense.

Twists then should only be deployed with the utmost care and caution. Not every story needs one.

“Everything ends. Your story does too.”

In 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years, the universe will reach maximum entropy and die. That is to say, everything ends. Your story does too. Videogames present unique challenges for endings, because they come in many forms. Some games have strict endings, while others have multiple endings depending on player input. You might get a sequel, that would be exciting wouldn't it? Others have no defined end in sight, running online for years, but will one day, eventually come to a close. So it’s good to think about what an end might look like.

Endings are a chance to provide closure, and usually have a strong link with the theme. Your story should probably resolve in some form. Audiences tend to have a fondness for happy endings, or at the very least bittersweet ones. Consider whether any of your characters deserve or have earned one, and what that might look like.

That said, it’s your show. Authorship means putting part of yourself onto the page (or in this case, screen) so if there’s any fundamental truth you were trying to convey, now might be the time to ram it home. Ultimately, endings are your last chance to say something to the player.

So, take these tips and go forth to write your stories. Write your truth. Tell us, tell me, tell the world...

... What is it that you are trying to say?

I'd like to thank the #writing channel of the UK Games Industry Slack. Their brilliant ideas and discussions have inspired some of these tips. For more about Etch Play and our commitment to extended experiences, check out this page or follow us on Twitter.